Venture Capital is Subsidizing U.S. Material Science Research

Venture-backed autonomous labs for now rival NSF’s annual budget for materials and chemistry

Updated 11/26/2026 to reflect Lila’s $200M seed round, which was also raised in 2025. Thanks to Calvin Li for pointing out this missing data point.

Materials are not charismatic technologies like cars or computers. Yet they enable almost every one of humanity’s technical achievements: rebar unlocked the skyscrapers of the 1920s; chemically strengthened glass delivered us smartphones; and stainless steel, not created until 1913, brought with it the clinical equipment upon which modern medicine depends.

Innovations in materials science drive technological competitiveness. They are among the most tangible ways basic R&D spending benefits consumers. From semiconductor design breakthroughs to steady advances in battery and solar materials, a healthy materials research ecosystem is essential for staying at the frontier of industrial technologies.

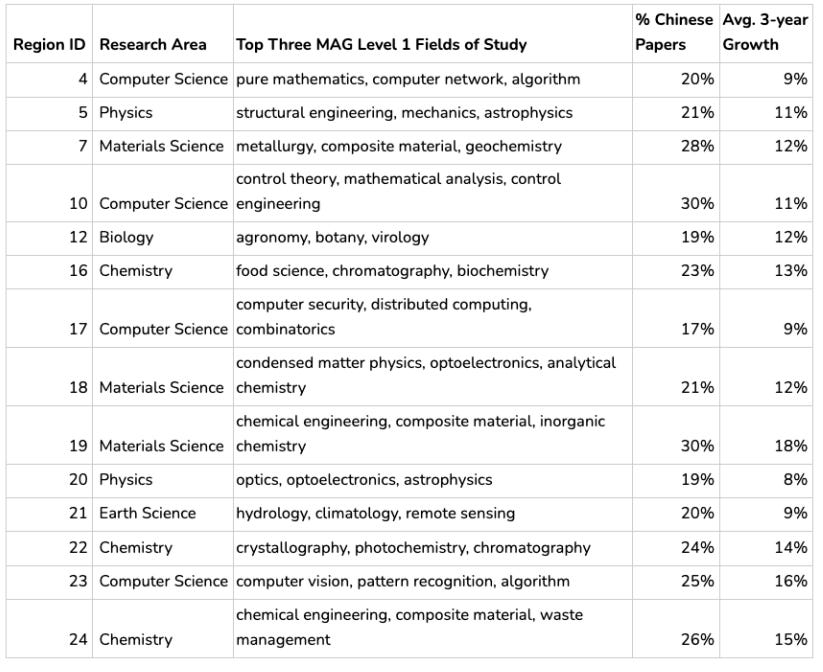

In the past decade, China has become a clear leader in material science research, through a combination of decentralized industrial policy subsidizing manufacturing investments, and investing heavily in science funding for key material science sectors.12 China has leveraged and coordinated the various arms of the government science apparatus to plug key material vulnerabilities, such as helium3 and rare earth refining4.

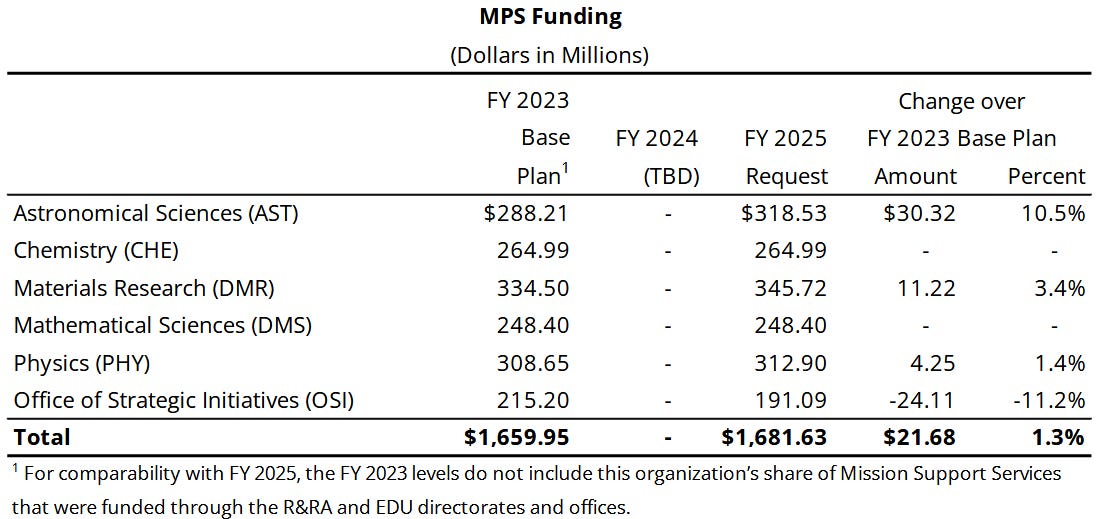

Meanwhile, the U.S. struggles to pass federal budgets on time, creating chronic uncertainty for federal science funding. The National Science Foundation’s (NSF) budget has stayed largely flat, eroded by inflation. 5 Layoffs and cancelled grants have further weakened the system, and visa restrictions have driven away international researchers who once sustained America’s talent advantage.6

So what does the turmoil in Washington DC have to do with San Francisco venture capitalists?

In the past year, the frothy AI venture capital investors have begun to normalize their AGI expectations and settle on AI for Science as one of the key growth markets for advanced AI technology, outside of code generation. For instance, just in the past few months at OpenAI:

Kevin Weil, formerly head of product at OpenAI, has transitioned to lead their AI for Science effort.

Liam Fedus, former VP of post-training at OpenAI, left to found an AI for Science startup (specifically, Periodic Labs).

AI for Science is in the air.

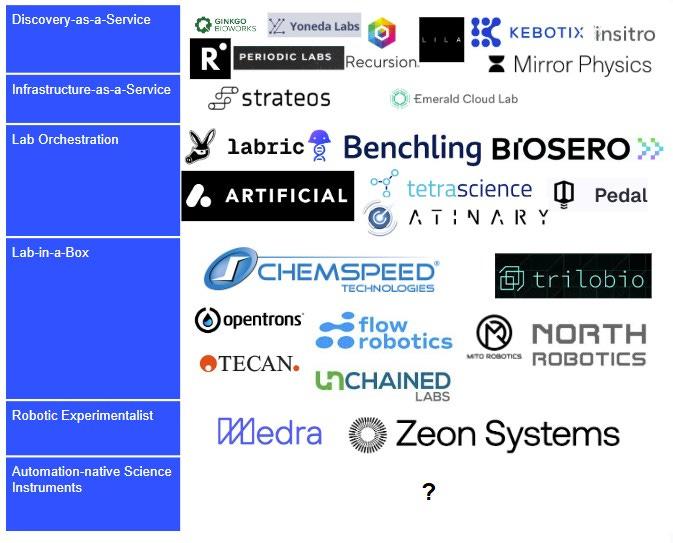

One critical part of enabling AI for Science is autonomous labs. As I have been writing about for years now, autonomous labs, which integrate robotics into science experiment workflows, are an important technology for accelerating material discovery, generating real-world training datasets for foundation model training, and giving AI agents autonomy in the physical world. While university researchers and national labs have been developing autonomous labs for several years, the startup ecosystem for autonomous labs is also increasingly active:

The Lab Automation Startup Ecosystem

Lab automation is beginning to attract a growing wave of startups. After years of academic prototypes and institutional research, it’s exciting to see more founders and investors enter the space — building companies that combine robotics, software, and AI to accelerate scientific discovery.

While VC funding historically went to large AI model developers like OpenAI and Anthropic, this past year has seen a dramatic shift towards also funding AI applications like AI for Science — to the benefit of autonomous lab development.

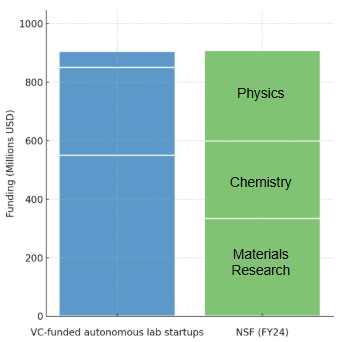

In this past year, the amount of venture investment into startups building autonomous labs for materials and chemistry is comparable to the annual NSF budget for materials, chemistry, and physics.789 10

Most of the VC funding to build autonomous labs is in Lila Sciences ($550M) and Periodic Labs ($300M), with a long tail of smaller startups.

It is somewhat beautiful that San Francisco VC’s are subsidizing scientific infrastructure build-out, such as autonomous lab development. It is even more ironic when considering that a non-trivial amount of VC in the U.S. today is foreign capital seeking American VC returns.

But let me be clear: public science funding, while never perfect, can not be replaced by VC money.

We do not need to present false choices between VC funding and public science funding. We should strive to have both robust public science funding and recognize the positive spillover from VC funding in AI for Science. We can recognize the unique capital markets America is endowed with and the importance of supporting public science funding. If we are serious about competing with China on the global stage for technological innovation, then we need to leverage every part of the toolkit.

Public funding remains essential for autonomous lab development. It operates on different incentives and timelines, supporting the long-term, cumulative work that startups depend on. Venture capital doesn’t train undergraduate or graduate students in materials science, or teach them to run precision instruments—that infrastructure exists because of public investment.

While frothy VC bubbles come and go—and are famously wasteful—public science funding remains the stable bedrock for sustained investment and talent. It anchors research and talent development across generations. Autonomous labs, while still underrated, are only one piece of the materials innovation ecosystem. National labs and university user facilities—home to the world’s largest beamlines and supercomputers—form billion-dollar public infrastructures equally vital to materials discovery.

Autonomous-lab startups will produce enormous quantities of experimental data, much of it kept proprietary. Publicly funded researchers, by contrast, have a mandate to share their data. For instance, AlphaFold was only possible because of open datasets generated at Brookhaven National Laboratory. If we surrender all autonomous lab development to the private sector, we risk starving the broader AI for Science ecosystem of the public data that fuels it.

In the coming posts, I’ll write about what philanthropy and public science funding can do to support the autonomous lab ecosystem.

Thanks to H.W. for inspiring this post.

In this 2021 CSET paper, they survey granular research clusters and identify which country has disproportionate leadership in each research cluster. China is disproportionately leading in material science and other STEM fields (shown below) whereas U.S. leads in far fewer research clusters, mostly in social science and biology.

https://www.scmp.com/news/china/science/article/3282295/china-quietly-extracting-itself-us-helium-stranglehold-experts-say

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s13563-019-00214-2

https://www.aip.org/fyi/fy2026-national-science-foundation

https://www.acenet.edu/News-Room/Pages/Proposed-Visa-Rule-Would-Hurt-Global-Talent-Pipeline.aspx

The graph only includes autonomous lab startups from the market map that raised in the past year and that focus on materials/chemistry applications.

One caveat: this is comparing annual NSF budget with venture rounds from this year, whose capital will be deployed over several years.

For instance: Radical AI, the #3 largest autonomous lab startup by cash raised, recently supported an open-source pytorch project for accelerating chemistry simulations.

another charles banger

I'd count this as a fun fact, but most of these AI startup "fundraises" are GPU swaps where most of the money is in compute and that serves as collatoral, so relatively little of it goes to the actual hard sciences.

I'm fully onboard for hoping AI funds a hard science revolution and am happy Charles is writing about this, but we need to see the balance sheets before getting too existed!

I'm much less bullish than you are here, but hopefully I can be proven wrong.