Antitrust & the Science Instrument Industry

And the Opportunity for an "Anduril for Science Instruments"

Anduril and the Last Supper

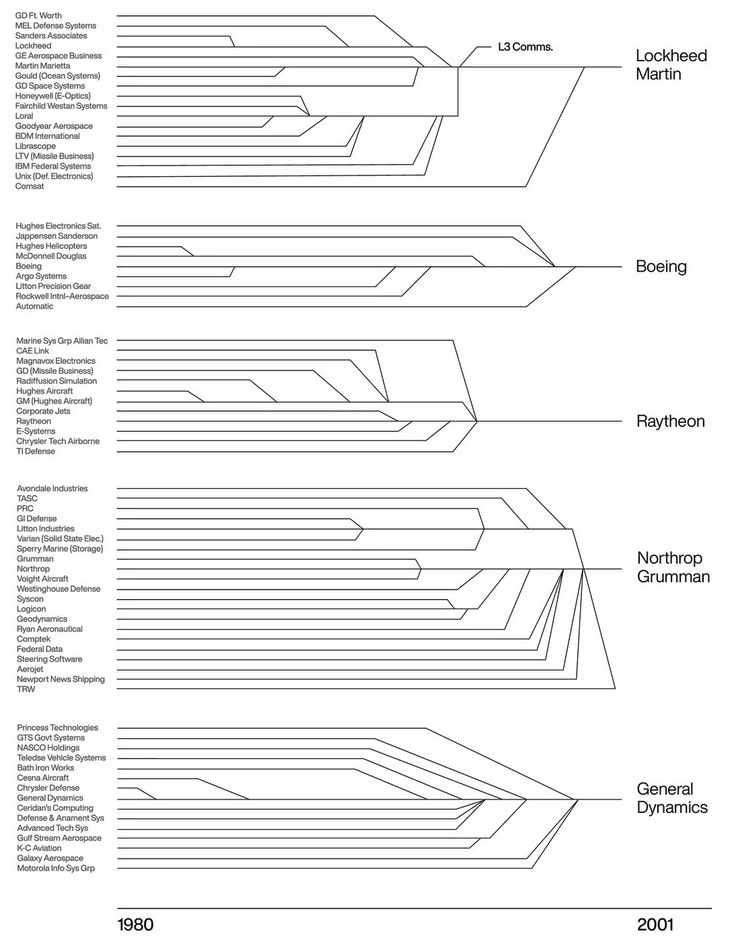

By now, many will be familiar with the story of defense prime consolidation. After the Cold War ended, 51 prime contractors merged down to 5, leading to less competition, slower development timelines, and ballooning costs. The government became dependent on a fragile oligopoly that struggles to surge production or innovate quickly.

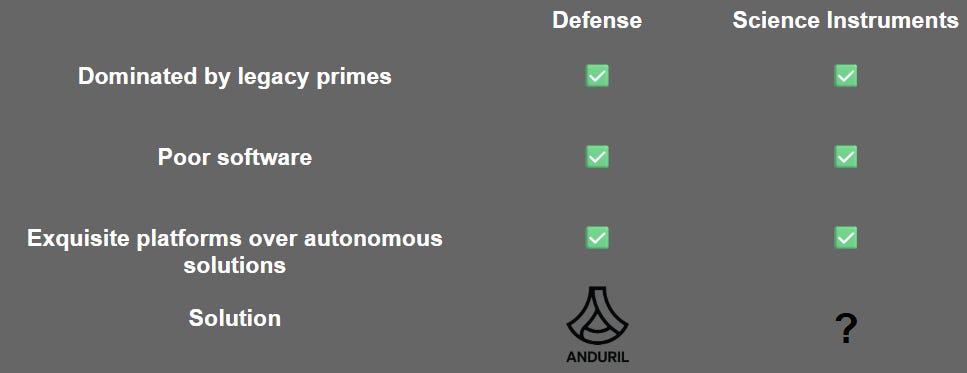

Anduril, a venture-backed defense tech startup now valued at $30B, was founded to disrupt these legacy primes. Their bet: that the need for good software and autonomous assets created an opportunity to disrupt the legacy defense primes still building fragile, exquisite platform systems.

Whether or not Anduril succeeds, the diagnosis and theory of change is striking—and as I’ve been digging into the science instrument industry, I found a surprisingly similar story playing out.

Consolidation in the Science Instrument Industry

When I first started my journey into autonomous labs1, I did so out of a conviction that they would play an important role in how AI accelerates scientific discovery. I quickly became convinced that science instruments—with their poor software APIs and lack of automation-friendly hardware—would be the primary constraint to realizing autonomous labs, particularly compared to the rapid progress in AI models and robotics.

Which is why I’ve been more recently writing about automation-native science instruments and even hosted a 2-day workshop on autonomous science instruments earlier this year.

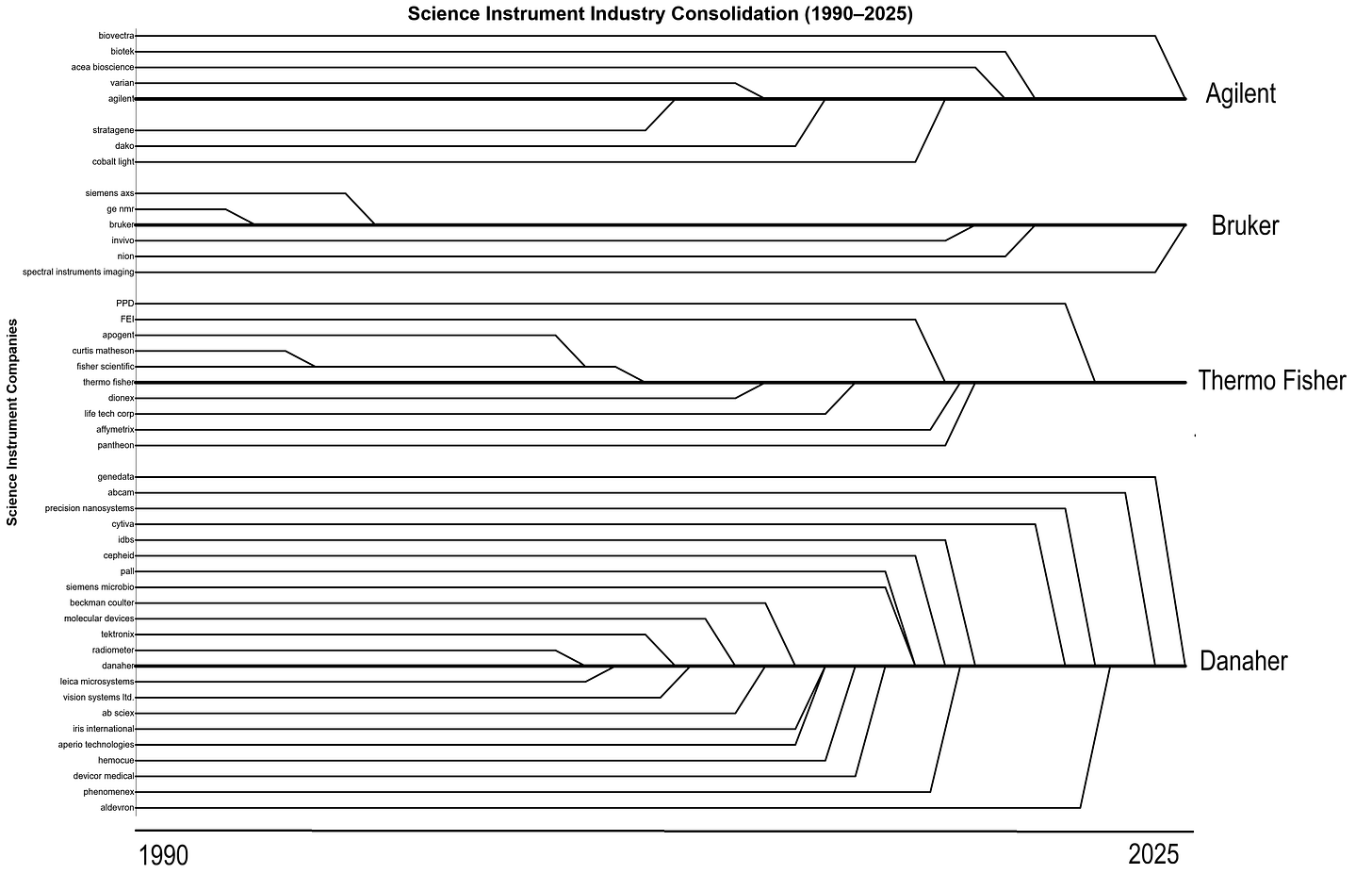

What surprised me as I learned more about the science instrument industry, was how often I ran into a familiar story: legacy primes who acquired and rolled up smaller companies, leading to expensive products with horrible software and high-cost recurring service contracts. Large science companies like Thermo Fisher are closer to science conglomerates, with bundles of subsidiaries acquired through acquisition.2 I was able to recreate the Last Supper M&A graph for the science instrument industry, looking at acquisitions from Agilent ($40B market cap), Bruker ($7B), Danaher ($160B) and Thermo Fisher ($200B). And the graph below is only a selected set of acquisitions.

Danaher is particularly unabashed about the role M&A plays in their ability to compete. Their annual report segments the company into Life Sciences, Biotechnology, and Diagnostics. Here is how each section begins:

Danaher established the life sciences business in 2005 through the acquisition of Leica Microsystems and has expanded the business through numerous subsequent acquisitions, including the acquisitions of AB Sciex and Molecular Devices in 2010, Beckman Coulter in 2011, Pall in 2015, Phenomenex in 2016, IDT in 2018, Aldevron in 2021 and Abcam in 2023.

Danaher established the Biotechnology segment through the acquisition of Pall in 2015, and expanded the business through the acquisition of Cytiva in 2020

Danaher established the diagnostics business in 2004 through the acquisition of Radiometer and expanded the business through numerous subsequent acquisitions, including the acquisitions of Vision Systems in 2006, Beckman Coulter in 2011, Iris International and Aperio Technologies in 2012, HemoCue in 2013, Devicor Medical Products in 2014, the clinical microbiology business of Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics in 2015 and Cepheid in 2016

This pattern of acquisitions and consolidation is often used by primes to improve their competitiveness in specific instrument lines.

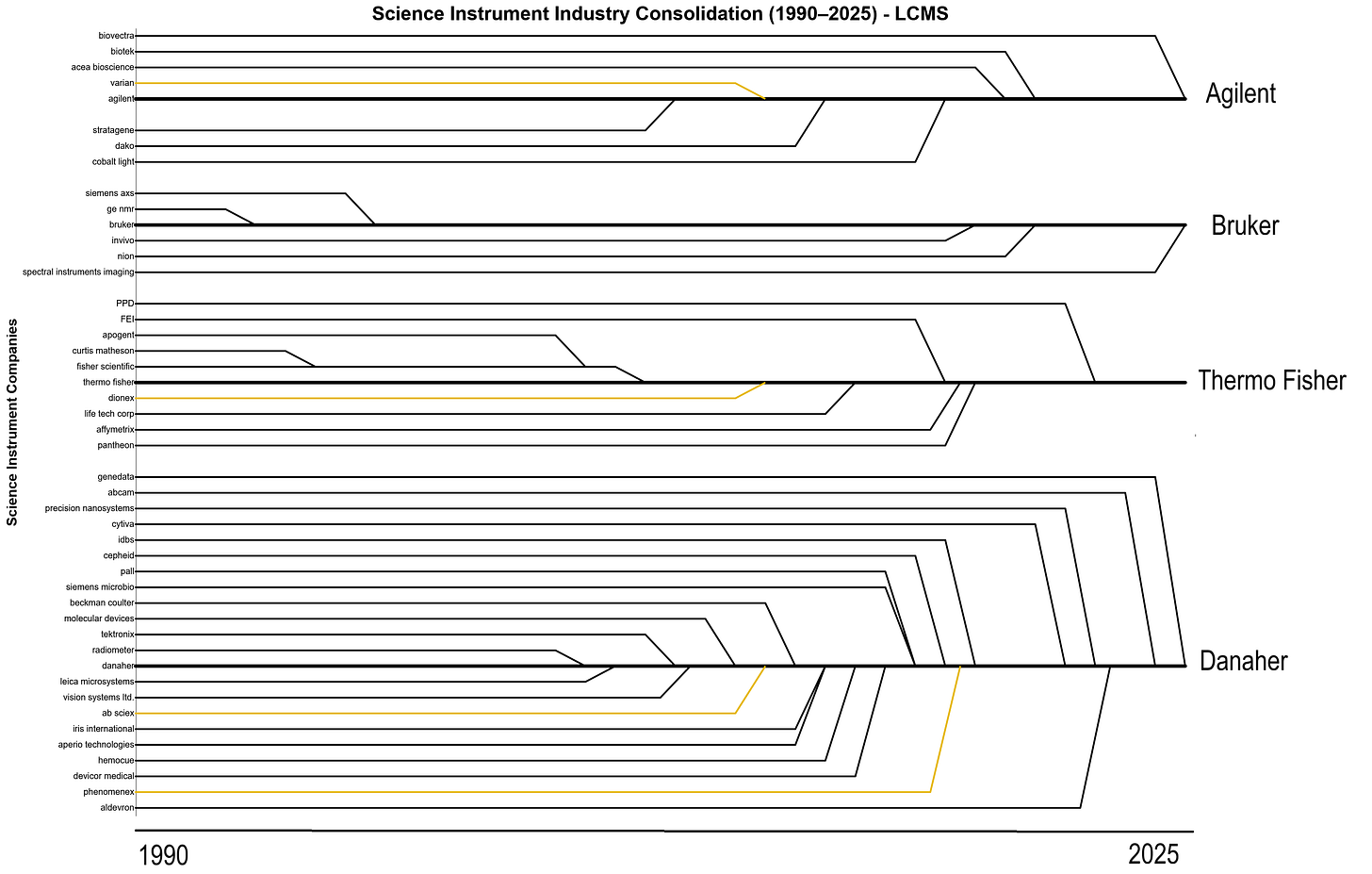

The Liquid Chromatography Mass Spectrometry (LCMS) sector offers a textbook example of strategic consolidation. Agilent, a long-time leader in Gas Chromatography MS (GCMS), acquired Varian in 2010 to in-house Varian’s vacuum pumps (a component in LCMS) and their LC column product lines. Meanwhile, Thermo Fisher—already the leader in Mass Spec—acquired Dionex to secure the ‘front-end’ liquid chromatography hardware, creating a fully integrated product offering. Then there is Danaher, the most aggressive acquisition player, which bought AB Sciex to enter the LCMS hardware game and Phenomenex to capture revenue from the consumables that run LCMS.

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) does occasionally take action in these acquisition deals. In the LCMS case, FTC required Varian and Agilent to spin off several higher end MS product lines to Bruker before allowing the 2010 acquisition to proceed.

The FTC has also taken action in other acquisitions, including Thermo Fisher’s 2014 acquisition of Life Corp (divest several products to GE Healthcare) and in the 2006 creation of Thermo Fisher (Thermo Electron merger with Fisher Scientific). In other words, the $200B world leader in scientific equipment was born through an antitrust-challenged merger.

Natural Gravity Towards Scale

There are real economic reasons why consolidation makes sense in the science instrument industry, and it would be intellectually dishonest to ignore them.

Sales and support overhead: Science instruments require extensive pre-sales consultation, application support, and field service. A single electron microscope might cost several million dollars and require specialist engineers for installation and maintenance. Building out a global sales and service network is enormously expensive, and there are genuine economies of scale in spreading these fixed costs across a broader product portfolio.

Low manufacturing margins: Instrument manufacturing itself operates on thin profit margins. Companies face strong incentives to create vendor lock-in, as the higher profit margin business lines are through providing integrated solutions and selling consumables. The margin incentive structure then naturally biases companies to expand beyond selling instruments towards growing into other business lines that provide higher margins.

Downsides and Disruption

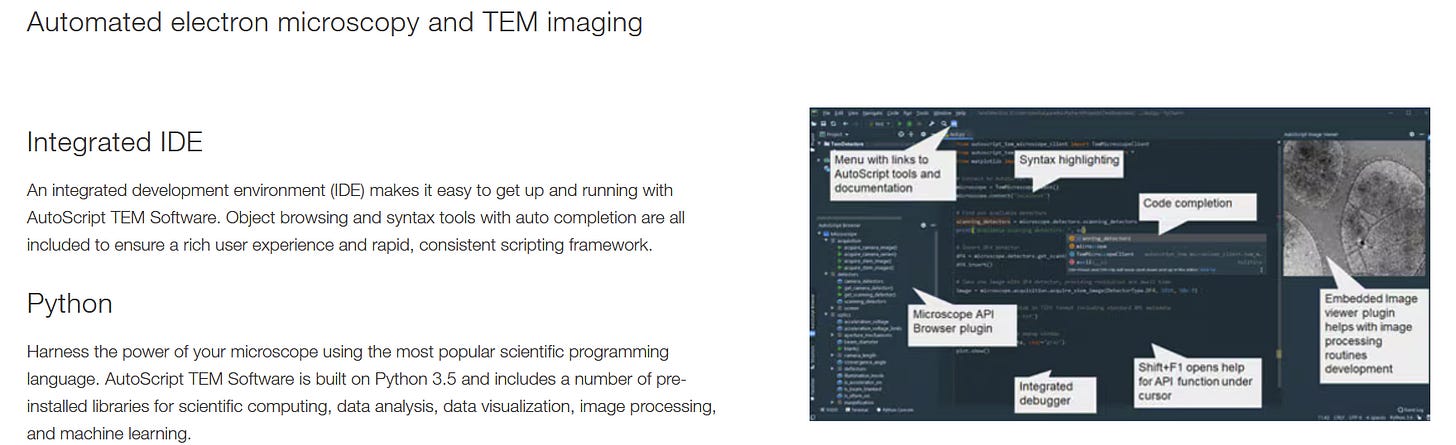

But this consolidation comes with costs that affect the future of autonomous science. The clearest symptom is the poor state of software for scientific instruments. For instance, Thermo Fisher markets “automated electron microscopy” solutions, but to actually automate anything you need to pay a license to use their Python API and their proprietary IDE. The state of the science instrument industry is such that in 2025, you pay millions for an instrument and a recurring service contract, then pay again for the privilege of having programmatically control over your instrument.

And this is not just Thermo Fisher or electron microscopy, but represents the broad trend across science instruments. During my workshop on autonomous science instruments, we heard from researcher after researcher on the pain of working with instrument software:

poor API documentation, if there even is an API

non-standard data formats, or even vendors encrypting instrument data that can only be decrypted with proprietary software

9-18 months of upfront development time spent just getting instruments to talk to each other through homemade drivers

Autonomous labs will not realize their full potential until there is a robust portfolio of science instruments that ship with open software APIs, standardized data formats, and hardware designed for robotic integration.

While antitrust scrutiny of acquisitions can help preserve competitive pressure, it often is only able to rearrange business units between the same set of oligopolistic primes.

To truly build automation-native science instruments will require Anduril-like disruption to a legacy industry that has not seen a new prime in 40 years.

Today, there is a billion-dollar opportunity to build automation-native science instruments: modern software and instrument hardware designed for robotic integration, built to power the future of autonomous labs. A few early-stage teams are starting to chip away at building autonomous instruments in specific product lines. But building the next Thermo Fisher will require understanding the market dynamics that let incumbents survive—and what it takes to break through.

If you’re interested in chatting more about an “Anduril for Science Instruments” — reach out!

Autonomous labs use robots to operate scientific equipment, enabling AI-powered closed-loop experiments.

And the market cap of Thermo Fisher ($210B) is larger than Northrop Grumman ($78B) and Lockheed Martin ($104B) combined!

Great article Charles! Experienced the janky SEM software issue first-hand during a materials science course. Great fusion of current political economy trends while acknowledging the trade-offs present in the argument.